Dead Ends: Life and work in the shadows of unsolved murders

Loose ends make a fertile breeding ground for rumour, suspicion and fear. And few loose ends linger in quite the same way as an unsolved murder. But what is it like to live and work in and around the scenes of unresolved horrors?

The case files of more than 1,400 murders currently linger unsolved upon the shelves of England’s police stations – their pages a chronicle of human endings in which the modes of killing – blunt force trauma, shooting, stabbing, strangulation – are stuck on grim repeat.

The oldest case dates back more than 100 years to 1905 and span every decade since.

Each killing wreaks immediate devastation on the families and friends of victims.

But these unsolved murders also leave more subtle psychological legacies upon the communities in which they take place, occasionally etched so deeply into the communal memory that they can come to define a place.

Neighbours

Within seconds of setting up the tripod, a man appears and asks protectively, though politely: “What are you doing here?”

You explain you are taking a picture of 98 Greswolde Road in Birmingham’s Sparkhill area, the former corner shop building where pensioner sisters Alice and Edna Rowley were found murdered 30 years ago.

Their killer stole just two boxes of chocolates, a bottle of Tia Maria and a radio cassette player.

“Ah yes, Edna and Alice” says Lloyd Archer, the man asking. “Terrible.”

He beckons over a second man – Denis Byrne – who is out walking his diminutive, three-legged, dog.

It might seem peculiar, but these two men not only know about the killing, they also know what others in the street know about the murders.

This network of knowledge, refined and agreed over many years through myriad neighbourly conversations, spans suspected culprits, theories as to what happened and knowledge of the sisters and their murder.

“There was a terrible feeling locally here,” says Mr Byrne, who lives opposite the corner shop. “They were two old ladies who never interfered with anybody, kept themselves to themselves.”

He tells of the ‘ha’penny jars of toffees’ and how they would sometimes treat children to a few freebies if they didn’t have enough money.

Eight years after the murders, the building was bought by Ahmed Khan and became an Islamic cultural and education centre. Mr Khan, who is also chairman of the centre, said he was fully aware of the killings when he bought the property.

He believes whoever killed the sisters – and he has his suspicions – was now dead. In the network of knowledge about the killings, some in the street defer to Thelbert Alleyne who, having moved in opposite the shop 63 years ago, is one of the area’s most established residents.

The day after the murders, his son Frank was stopped by police on his way back to the family home for Christmas.

It was there, in the middle of the street, that Frank learned the two old “lovely ladies” (whose chin whiskers had intrigued and fascinated the area’s younger residents) had been murdered, “It (the shop) is part of my childhood and memories,” he said.

“If you had five or 10 pence you’d pop over to Rowley’s for sweets, and if you didn’t have enough they’d always let you have something.

“You’d go in through the door and see into the back, they’d be in the back area and would come through and serve you when they heard the bell.”

“In those days it was a very close community,” he says. “Everyone on this street, everything on this street, was known to everyone.”

He raises his head and beams a knowing smile at the suggestion this still seems to be the case.

__________

The Successor

Shortly after midnight on 8 September 1963, pub landlord and former miner George Wilson took his dog out for a walk.

Just 20 minutes later, his wife Betty found him outside their Nottingham pub with horrific stab wounds to his face, neck, head and back.

Mr Wilson died at the scene.

His death – which came to be known as the Pretty Windows murder (because of the attractive glasswork at Mr Wilson’s Fox and Grapes pub) shocked the city and triggered one of the biggest manhunts ever carried out by Nottinghamshire Police.

A few months ago the pub – whose name changed to Peggars after the murder – re-opened under its original name: the Fox and Grapes.

The new manager is Danylo Semak, born and raised in Nottingham.

“I thought I would be asked about it,” he said. “Some people have asked me whether I am feeling lucky.

“But in general people do not talk about the murder quite as much as I thought they would.

“It happened and we understand it happened, but as far as I am concerned it was many years before I was born.

“That is one thing we have tried to do – be sensitive towards it and acknowledge it but not sensationalise it in any way.”

The urban landscape surrounding the pub is shifting. What was, in Mr Wilson’s day, an enormous wholesalers’ market, is now being re-imagined as the city’s ‘Creative Quarter’, an incubator a new breed of independent businesses.

But the process is incomplete. New artisan shops and coffee houses sit within a stone’s throw of terraced rows of derelict red brick units. This flux exists not just in the bricks and mortar but in the community’s collective memory of the Pretty Windows Murder.

Step into the offices of those directing the Creative Quarter initiative and the chief executive officer Stephen Barker will explain how the murder is rarely mentioned partly, he says, because of many years of incomers into the city post-1963.

But linger for 10 minutes in that same office, and people’s memories, questions and stories about the murder start to seep out: theories as to motive; whether the killer knew Mr Wilson’s dog walking routine; whether it was a targeted murder.

Just one of the original ‘pretty windows’ from the Fox and Grapes remains – preserved within a wooden frame inside the pub.

No plaque proclaims its presence. But those for whom this ‘pretty window’ matters – or to those curious enough to ask about it – know it is there, rather like the unsolved murder that bears its name.

__________

A Mother

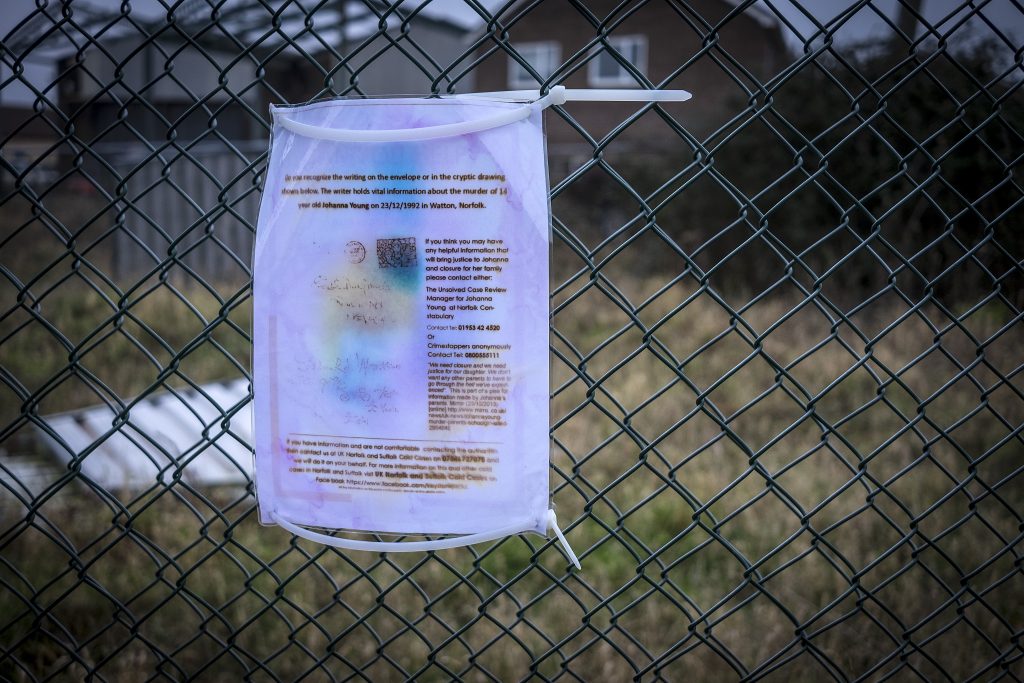

As the crow flies, the mother of Johanna Young lives less than a mile from the water-filled pit in which her 14-year-old daughter’s body was found on Boxing Day in 1992.

Yet in the 25 years since the killing Carol Young has never visited the scene in Griston Road, in the small Norfolk town of Watton.

“I have never felt the need to,” she says.

Johanna’s parents last saw her on the cold and foggy evening of 23 December.

Two days later the teenager’s shoes were discovered in undergrowth by a dog walker. Soon after her body was found nearby.

Johanna was lying face down in water with her lower clothing removed. The cause of death was drowning and a fractured skull.

Her killer or killers – Mrs Young believes more than one person was involved – have never faced justice.

Remaining in the place where a daughter had been murdered might have been too much to bear for some families.

The Youngs have stayed put, Mrs Young says, in part to look after her mother but also because Watton is their home.

“Some people speak to me about it, some people don’t,” says Mrs Young. “I don’t really mind either way.

“Most of the time it is fairly quiet. But then there is a piece in the newspaper about it, or a fresh appeal, and then people will talk to me about it, saying things like they wish us luck or hope the police find something this time.”

The Youngs remain haunted by the many unanswered questions.

“She was still alive when she was dumped in the water,” says Mrs Young.

“They should have sought help or at the very least just left her. She might still have died but maybe not.

“It is with you all the time – why did they dump her in the pond? Who did it? Why? Were they alone?”

The Youngs know their daughter’s killer is not only still at large, but is probably nearby.

“You do wonder if the person you just passed in the street was the killer.”

__________

The ‘old guard’

Edna Harvey, who lived alone in a ground-floor flat in the horseshoe-shaped Finchley Road in Ipswich, was not well known to most of her neighbours.

This was not because the 87-year-old was in any way anti-social, but because she was nearly blind and extremely frail and rarely ventured beyond the confines of her flat.

That frailty, and the fact Edna lived a simple life with meagre possessions, made the brutality of her murder in August 1984 all the more shocking.

Edna’s killer or killers strangled her before setting her alight on her mattress.

More than 30 years on, Frank Culham remembers the murder vividly.

“The police were going around knocking on all the doors asking whether anybody had seen anything.

“It was so very sad. Back then it was so nice and quiet here. Things altered.”

Memories of Edna are vanishing fast, but unlike with the Pretty Windows murder, or the killing of the Rowley sisters, it seems the story of her death is not being passed on to newcomers.

The reason, according to the street’s self-proclaimed “old guard”, is that the sense of community they once enjoyed has long been shattered.

Edna’s death and the suspicions it aroused are felt to have played a role in the dissipation of that social cohesion.

Molly and Michael Adams, who live a few doors down from Mr Culham, moved into Finchley Road more than 50 years ago.

Back then, they say, neighbours would sit out in their front yards sharing their news and views.

“We do still think about her,” says Mrs Adams.

“Whenever there is an unsolved case on television or in the paper, we wonder what happened to her and who could have done such a thing – she didn’t have much and she could barely see.

“This used to be a really strong community. In 1977 the whole street organised a party and we had the whole road closed off. On New Year’s Eve we would get together and do the conga in the street. We’ve drifted apart, things have changed.

“We knew about Edna from Sylvie, who was her carer. Sylvie has since died, as have quite a few other people who remembered the case.

“There are not many of us left who remember what happened.”

_________