The bomb hunters scouring UK waters for unexploded weapons

Hundreds of thousands of unexploded bombs and mines carpet the seabed off the UK’s coast. Many are known about and mapped, but plenty more are not, posing a potential danger to those working at sea. It is Lee Gooderham’s business to find them.

The map projected onto a screen at an industrial estate in Norfolk is the result of 12 years’ work.

As Mr Gooderham, founder of Hethel-based Ordtek, zooms in on the English Channel and the southern North Sea, thousands of tiny red dots emerge like scattered confetti.

“Each of those dots is a reported munition,” he says. “We are talking hundreds of thousands of items.”

What the map does not show are all the unknown munitions still lurking on the seabed.

“We are finding unexploded ordnance and dealing with it on a daily basis,” Mr Gooderham says.

“There are many that we don’t know about.”

Despite being dropped – or dumped – decades ago, unexploded ordnance (UXO) continues to pose a very real danger to those working in our waters.

“The real problem is when fishing vessels and dredgers encounter unexploded ordnance,” says Mr Gooderham.

“That is when it becomes dangerous.”

In 2020, fishing vessel Galwad-Y-Mor was thrown into the air when a World War Two bomb exploded 25 miles (40km) north of Cromer, Norfolk.

Five crew members were injured, including one left blinded in one eye.

Skipper Lewis Mulhearn, 39, won a bravery award for saving the lives of his crew.

Mr Mulhearn, who suffered three broken vertebrae, sternum and orbital bone in the explosion, died in January 2023.

Mr Gooderham’s clients, however, are not from the fishing industry, but the offshore and renewables sector.

“Some of their early sites in particular were in high-risk UXO areas, such as Thames Gateway, Gunfleet Sands and those type of areas,” says Mr Gooderham, whose firm is one of a small number offering consultancy for UXO.

“All of a sudden they were looking to put cables and assets out into the sea in these high-risk areas and, of course, they hadn’t really considered that there could be UXO there.

“Scroby Sands, Gunfleet Sands, London Array – all of those got built, very near shore, in high-risk areas.”

The job of finding UXO starts with desk-based work and archive research.

“Once we know there is a risk there and there is a problem, a survey is carried out,” Mr Gooderham says.

“This involves sending out a vessel with geophysical equipment, a magnetometer, and we oversee that – we are on board the vessel.

“We’ll get the data back to the office where it will be processed and they’ll say ‘We think this is a bomb, that is a bomb, this is a bomb – you need to do something about it.'”

If bombs can be avoided by a minimum of 10m (32ft), they can be left in situ.

“By the time it is on the seabed, it is safe. It is not going to blow up, unless it is interfered with,” says Mr Gooderham.

“If it cannot be avoided, we use another vessel with a remotely-operated underwater vehicle (ROV).”

Before munitions are detonated, the ROV gently moves sea life, such as crabs and lobsters, out of harm’s way.

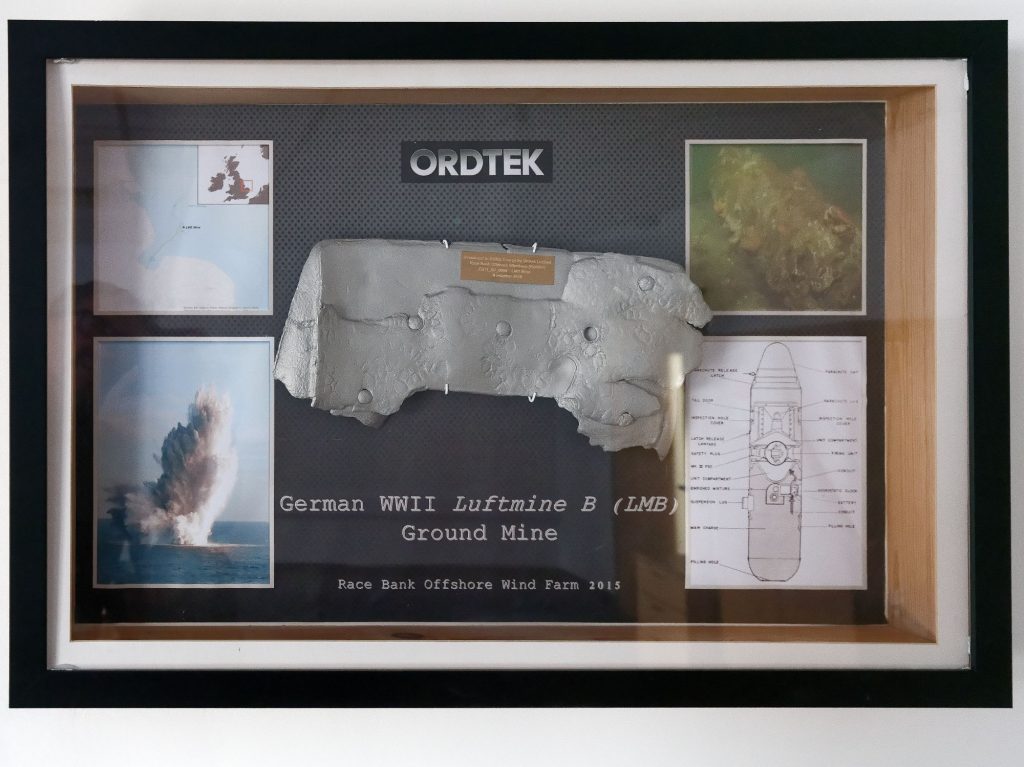

An example of the bomb-hunting process hangs on the wall of Ordtek’s offices.

The munition fragment was found at Race Bank, off the Norfolk coast.

“In this situation we had this target, we predicted it was a bomb and it was, it was this German mine in 25m (82ft) of water, 700kg (1,500lbs) of explosives,” says Mr Gooderham.

“It made a 50m (164ft) to 70m (229ft) plume when detonated.”

Once the item is destroyed, any debris over 30cm (12in) wide must be collected and properly disposed of.

The whole process, says Mr Gooderham, can cost hundreds of thousands of pounds.

“What is really interesting is when we get abnormal finds, like these dump sites that we did not know were there,” he says.

“On one project we came across a 4,000lb (1,800kg) bomb, which is very rare. It was a very big bomb, it was British but why it was there we just don’t know.

“It was so big it could not be destroyed because of various permit-related issues. It remains there and it is monitored. That was a surprise – when you find a 4,000-pounder, it is a big moment.

“The largest ones you usually come across are the 1,000lb (450kg) bombs.

“The German munitions we come across are often as good as the day they were dropped. The integrity of the explosive within remains intact.”

But clearing the entire seabed would be nearly impossible, he says.

“The German government is looking at this at the moment and it is an unbelievable task.

“They predicted it would take 300 years to clear the seabed of munitions from World War Two and it would cost numbers that are off the chart.

“The interesting thing we are seeing are the numbers of unrecorded dump sites all the way from Gunfleet Sands up to the Hornsea Project, which are level with Hull.

“It is not a very good look for the British military; at the end of World War Two, they just got rid of it.”

While the renewables and offshore energy sectors pay for the work of firms like Ordtek, Mr Gooderham is keen his team’s mine-mapping work is available to others working at sea.

They include people like fourth-generation fisherman Steve Stoker, who has caught dozens of unexploded bombs off the Essex coast.

“I caught two in a week once,” says Mr Stoker.

“You usually know when you’ve caught a bomb in your nets and you mark it on your GPS and keep away.

“We don’t come across them as often now, mainly because we don’t wander as far, because there is not as much fish about so we tend to stick in one area.”

His great aunt and great uncle, Horace and Lily Stoker, were killed by a mine in the 1940s while out trawling.

“I know of a couple of boats which have had a bomb explode. One, in Lowestoft, had the bomb go off in the net and it blew the engine off its bed,” he says.

He also remembers the days when fishermen were paid for the UXO they came across.

“We used to get a lot of unexploded bombs at the entrance to the Thames,” Mr Stoker says. “We used to get money for it because they did not want us to chuck them away.

“The Royal Navy used to come down. They’d stay at The Victory [a pub]; they were good old boys and we had some good laughs with them.

“You would put a buoy on it and then leave them [the ordnance] somewhere shallow, take the Royal Navy out to them and they would set the charge and you’d go a certain distance out and they would detonate it.

“They used to go a hell of a way up in the air.

“Then it all changed and they didn’t want you to take them out any more – instead they wanted the police to take them out.”

Despite the inherent dangers of unexploded munitions, Mr Stoker says he has “never been worried about them, really”.

“I used to take a day off from school to go out with my dad and blow a bomb up,” he says.

“It was quite a regular thing. I learned not to be afraid of them and to not worry.”

A Ministry of Defence spokesperson said: “At the end of World War Two, munitions were disposed of in a variety of places and they continue to be discovered to this day.

“Our explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) teams always respond and deal appropriately with any materials discovered.”

Originally written for the BBC News website and published on 22 January, 2024